This blog post by Bella Mirabella explores the handkerchief, for early modern women a highly significant accessory.

By Bella Mirabella

In his 1558 book, Il Galateo, Giovanni Della Casa offers the following advice about the handkerchief:

And when you have blown your nose you should not open your handkerchief and look inside as if pearls or rubies might have descended from your brain.

With this comment Della Casa touches on one of the more practical uses of the handkerchief, while also giving advice about the proper etiquette associated with this small but very important piece of cloth. In another vein, John Stowe writing in England in 1580 observes that women often give their “favorites” “little handkerchiefs of about three to four inches square, wrought round about with a tassel at each corner”; the men put these love tokens in their “hatbands” for all to see.

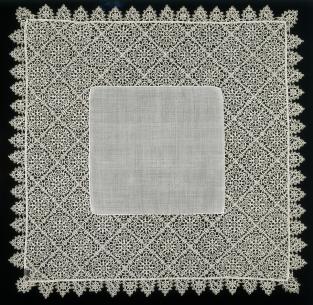

As these two examples reveal, the handkerchief in early modern Europe was a complex accessory and one with multiple uses: it could be a receptacle for bodily fluids and filth from mucus to tears to blood to sweat, as Della Casa indicates; it could be an essential agent of compassion and healing as the legend of Veronica wiping the blood from Jesus’ face illustrates. In drama we recall the delicately embroidered hanky Desdemona offered to Othello to cure his headache. The handkerchief could also be a sign of woman’s domestic work associated with the art of needlework, a desired gift, and an item that repeatedly shows up in wardrobe and dowry lists. In mountebank performances, handkerchiefs were the means of exchange during the transaction where money was passed to the stage and remedies in turn sent to members of the audience. A handkerchief could be a disguise for bandits, a sign of flirtation, and a token passed between lovers, as Stowe notes. The handkerchief was also a symbol of cleanliness and beauty, found in the hands of ladies of good breeding and fine taste, such as Eleonora di Toledo (image 2), or perhaps a sign of sexual transgression when found in the hands of prostitutes and courtesans (images 1 and 6).

As these examples make clear, the handkerchief is a complicated accessory, particularly with regard to gender. Men used handkerchiefs too—see the many portraits in which men have a handkerchief in hand or in a little purse, hanging from their belt, such as Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester (image 3). However, if we look at the many portraits of women holding hankies, or literary and dramatic references in which the handkerchief appears, we realize the deep contradictions embedded in the use of the handkerchief for women; in fact, I suggest that the uses of the handkerchiefs parallel the many and often paradoxical roles that women were expected to play at the time.

Male writers of the time, desperate to understand, define, and restrain women, often found themselves arguing between extreme views of the female. Consider Baldesar Castiglione’s third book in The Book of the Courtier (1528), which focuses on the debate over women. While one male speaker says that women are imperfect and defective and will lead men to their moral and physical demise, another, the Magnifico, counters that women are paragons of virtue who will elevate men to truth and nobility.

According to Castiglione, well-behaved Renaissance woman understood that morality, virtue, and good manners were always bound up with and mediated by grace. For women grace is in part attained through beauty, and grace comes perfectly into play when the female can use all of her lovely traits to “entertain graciously every kind of man with charming and honest conversation.” But the Magnifico quickly realizes that this quest has its erotic elements and can lead a woman into dangerous territory. Therefore, he advises that women “observe a certain difficult mean, composed” of “contrasting qualities,” and that they “take care not to stray beyond certain fixed limits.” This advice encapsulates the dilemma early modern women faced and reflects the uses of the handkerchief, which needed to mediate between the transgression of being a receptacle for bodily excretions and a silken cloth emblematic of virtue, good taste, and excellent manners.

The constant appearance of the handkerchief indicates that it was a popular accessory in the material culture of Renaissance Europe, an indispensible accessory to be held and possessed by all who could get their hands on one. But although it reached heights of popularity in the early modern period, the handkerchief had been in use for quite a while, waved, for example, by Romans at public games or court functions. In one of his poems the Roman poet Catullus mourns the loss a stolen napkin/handkerchief, which had reminded him of friendship and dear friends. And Juvenal writes about a wife who is threatened from banishment from home because she is always wiping her nose.

Later, from the 1300s through the 1500s, more advice appears which emphasizes both the necessity and use of the handkerchief in an effort to manage those bodily excretions. This was clearly an important task for servants, who had to use a handkerchief to wipe his or her nose rather than blowing into their hands. Erasmus also counsels how to manage “the filthy collection of mucus” that can haunt the nostrils in his 1530 book of manners for boys, De Civiliate Morum Puerilum. According to the French dancing master Thoinot Arbeau, it is important to spit and blow one’s nose infrequently but if you need to do so, a handkerchief is indispensible. And Della Casa adds that it is “disgusting” to offer anyone your handkerchief, even if it is clean. Della Casa warns that, if a friend had loved you, once you offer the handkerchief, “he is likely to stop then and there.”

These examples illustrate how the handkerchief is clearly associated with decorous behavior but also how it played an important role in the pursuit of cleanliness. Cleanliness indicates control over the body and a sense of order over disorder; it also carries moral implications. For Torquato Tasso, cleanliness conferred dignity, as well as nobility. Since appearance was crucial to public regard and respect, unsoiled linens, like a clean handkerchief became the visible symbol of the marriage of cleanliness and morality, good behavior and civility. When Lady R-Mellaine completes her wardrobe, she is certain that along with her gloves, purse, “mask, fan Chayne of pearls,” she has a “clean handkerchief.”

The handkerchief had its role to play not only in the pursuit of cleanliness but also in the pursuit of a more perfect world. In fact, the handkerchief was such an important and ubiquitous fashion item in the Renaissance, not only because it was so closely tied up with morality and the practice of fine behavior, but also because it promised the possibility of true nobility for those who held it. To writers like Castiglione and Della Casa good manners are outward signs of inner virtue. In fact, Della Casa argues that decorous behavior is the practical way to attain nobility since it must be followed each day, “whereas justice, fortitude” and other great virtues are only infrequently called upon. Even earlier than these two male writers, Christine de Pizan, in her Treasure of the City of Ladies, written in 1405, understood that the purpose of good manners, particularly for women was to perfect virtue and nobility and, hence, be well regarded. The handkerchief used daily and held in the hand for all to see, is a most visible sign that the holder possesses virtue. De Pizan well understood that women were vulnerable to the accusations of immorality and poor behavior; her book is devoted to counter this by arguing that women are capable of honorable behavior. The handkerchief offered a small, but practical and powerful image to counter this negative attitude.

If we briefly look at the dramatic examples of Desdemona in Shakespeare’s Othello, and Celia in Ben Jonson’s Volpone we see how the handkerchief moved between notions of virtue and potential vice. In Act 2 of Jonson’s play, Volpone has disguised himself as a mountebank, performing under the window of Celia, the wife of the wealthy merchant Corvino, with the intended purpose of seducing her. After presenting a brilliant imitation of a mountebank harangue, Volpone comes to the selling of his miraculous unguent, a cure for most ills, including aging, weakness, and sexual difficulties. Celia watches from her window and is eager to buy the cure with the help of her handkerchief, particularly after Volpone promises a “little remembrance” to the first person to “grace” him “with a handkerchief.” But when Corvino crashes into Celia’s room, pulls his wife from the window and disperses the mountebanks, he accuses his wife of being “an actor” with her handkerchief. Corvino is angry because Celia’s desire to purchase the unguent with the help of her handkerchief takes her into the public eye—at the window—which allows her to participate in the public sphere with one of her most intimate of linen objects. The handkerchief, carrying with it both the memories of its more unsavory uses and its symbolic value of purity, here transports filthy lucre, as it were, which is taken by the lecherous Volpone, who then fills the hanky with a fluid of his own making, and sends it along with a kiss to the female he hopes to seduce. Corvino’s anger at Celia’s performance at the window indicates that he thinks the handkerchief contains his wife’s body, transported from hand to hand in a public transaction. Further, rather than constraining her behavior, the handkerchief enables her to act.

In many ways this response is similar to Othello’s. When Othello gives Desdemona the handkerchief, he has certain expectations about how the love token would control and contain his wife’s behavior. As things unravel for him, he reminds her of its exotic and powerful origins. Given to Othello’s mother by an Egyptian, sewn by a sibyl, “dyed in mummy,” a medicinal liquid made from “maidens’ hearts,” the strawberry-studded handkerchief is not a simple piece of cloth. Othello’s expectations are that Desdemona will treasure the token remembering that it has the power to either make her “amiable” and “subdue” her to her husband, or, if she loses it, become “loathed” by her husband who in turn must “hunt / After new fancies” (3.4.57-76). In the beginning of the play Othello expects that Desdemona will adhere to the purity and modesty that the handkerchief represents but, as his expectations are not met, he is quick to abandon that notion and embrace the darker side of the accessory. Reproaching Desdemona with “Oh, thou publick commoner,” Othello conflates his wife with the handkerchief. Like Corvino, Othello “sees” his wife passed from man to man just as the handkerchief is in the monetary transaction.

As I have been suggesting, the handkerchief was a complex accessory, moving between public and private, virtue and potential vice. As such the handkerchief gave women some control over their actions and how those actions were perceived. The cloth accessory was a sign that women understood and participated in the discourse of manners and morality and symbolized their ability to attain beauty and virtue, even if the more unsavory elements of the handkerchief remained a threat.

Further Reading

Thoinot Arbeau, Orchesography, trans. Mary Stewart Evans (New York: Dover, 1967).

Bryne (Muriel St. Claire), ed., The Elizabethan Home Discovered in Two Dialogues by Claudius Hollyband and Peter Erondell (London: Methuen, 1949).

Baldesar Castigione, The Book of the Courtier, trans. George Bull (New York: Penguin, 1976).

Giovanni Della Casa, Galateo, trans. Konrad Eisenbichler and Kenneth R. Bartlett (Toronto: Center for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 1986).

Christine de Pizan, The Treasure of the City of Ladies or the Book of the Three Virtues (London: Penguin Books, 1985).

Desiderius Erasmus, De Civiliate Morum Puerilium, Collected Works of Erasmus, ed. J.K. Sowards (Toronto: University Press of Toronto, 1985).

Ben Jonson, Volpone, ed. Philip Brockbank (New York: W.W. Norton, 1968).

Bella Mirabella, “Embellishing Herself with a Cloth: The Contradictory Life of The Handkerchief,” Ornamentalism: the Art of Renaissance Accessories (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011).

William Shakespeare, Othello, ed. E.A.J. Honigman (London: Bloomsbury Arden, 2000).

John Stowe, The Annales or a generall chronicle of England…continued by Edmund Howes (London: 1558, 1631).

Cesare Vecellio, The Clothing of the Renaissance World-Europe, Asia, Africa, The Americas, trans. Ann Rosalind Jones and Margaret F. Rosenthal (London: Thames and Hudson, 2008).

Bella Mirabella is a professor of literature and humanities at NYU Gallatin and director of the Gallatin Humanities Seminar in Florence. She is editor of Ornamentalism: The Art of Renaissance Accessories, co-editor of the Arden book Shakespeare and Costume (Bloomsbury, 2016), and has written articles on women, performance, and sexual politics in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.