In this blog post, Susan Carlile explores Charlotte Lennox’s groundbreaking work on Shakespeare, which made her one of his first editors and literary critics and also allowed her to formulate her take on authorship and use of source material in writing.

By Susan Carlile

“Why Shakespeare?” Countless readers from around the world have asked what made his plays stand out above those of so many of his successful contemporaries. In fact, the sorting process that determined worthy “intellectual” content and selected authors of great merit who came to be called “geniuses” emerged in the 1700s. Privileged men who had the luxury and contacts to publish their own assessments weighed in, becoming the first-line promoters of what would become the English canon. The expanding British empire hungered for a national literary hero, a Dante, a Cervantes, to bolster the growing nation’s cultural status on the Continent. These early eighteenth-century literary critics would be responsible for setting in motion the brand that would soon dominate English letters, Shakespeare. Scholars were not the only ones who adored the author they began to call “the bard.” There was also something about Shakespeare that caused audiences, even one hundred years after his death, to flock to theaters for Macbeth, King Lear, Much Ado About Nothing, and so many others. By one estimate 1 in 6 theatrical performances in London between 1701 and 1750 was a play by Shakespeare, though many were radically adapted to fit modern audience tastes and most were not known to be by Shakespeare (Dobson, 2 and Hume, 43)

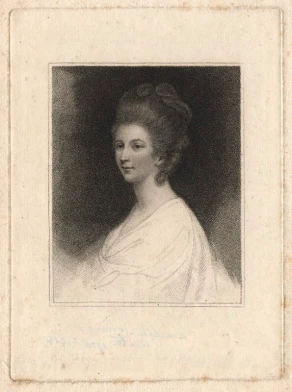

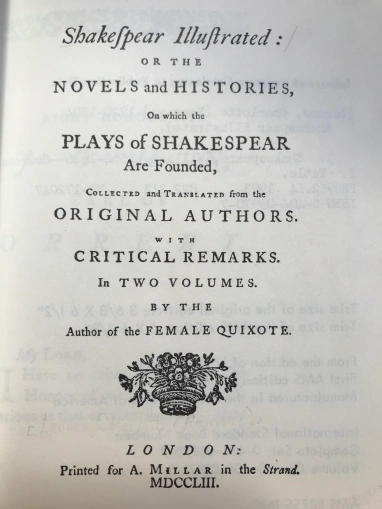

Onto this London stage stepped Charlotte Lennox, the twenty-four-year-old daughter of a now-deceased captain of the British fort in Albany, New York. An orphan who boasted a strong publishing record in London, Lennox not only researched the origins of twenty of Shakespeare’s plays and reminded audiences that Shakespeare himself was adapting prior plots, but she also printed with a leading publisher her own translations of these texts from French and Italian, her own studies of Latin and Danish texts, and her personalized commentary about Shakespeare’s genius, under the title Shakespear Illustrated (1753-4). She was dramatically expanding Gerard Langbaine’s systematic search for sources in 1688. Today we identify numerous source texts for Shakespeare’s plays, but Langbaine was the first to begin this catalog. He listed twelve sources and published a seventeen-page inventory of his findings, noting “many things will escape my observation. However, this may serve for a hint to others; who being better vers’d in Books, may build upon the Foundation, which is here laid” (Preface). Lennox’s far more extensive three-volume publication was an extraordinarily impressive feat of scholarship. Hers was not simply source study. She also articulated power relations by drawing attention to women’s dignity and criticizing the plausibility of some of Shakespeare’s female characters.

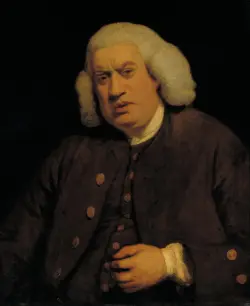

Some have argued that Lennox’s work was at the bidding of Samuel Johnson, who had begun crafting his own commentary about Shakespeare’s plays. But Lennox was already an accomplished author, having published a book of poetry (1747) and two novels, the second of which, The Female Quixote (1752), was making her a genuine celebrity. Lennox and Johnson arrived in London in the mid-1740s to a literary scene in upheaval. Although initially she may have been nudged by Johnson to research Shakespeare’s source material, Lennox’s experience as an actress helped refine her understanding of Shakespeare’s task. She performed popular female roles as audiences were increasingly exposed to women acting. Lennox was quick to capitalize on the public literary rage that was growing around Shakespeare. In fact, Arthur Murphy declared, “With us islanders Shakespeare is a kind of established religion in poetry” (Vickers, Volume 4, 1753-1765, 1). Lennox’s acting experience as well as her novelistic celebrity ideally positioned her to publish a book about Shakespeare.

Not only seeking to capitalize on audience taste and enthusiasm, Lennox was also interested in serious literary criticism and specifically in his construction of narratives. Scholars reference Holinshed’s Chronicles as an important influence on Shakespeare, and Lennox “translated” (her words) Holinshed to illustrate how it was a source for Macbeth, Richard II, Richard III, and Henry the 4th, Henry the 5th, Henry the 6th, Henry the 8th, and King Lear. She also provided a Cliff’s Notes-type summary of both Holinshed’s history and Shakespeare’s adapted plots. But Lennox didn’t stop there, she found source texts in French, Italian, Latin and Danish and thus made it abundantly clear that Shakespeare crossed borders for his narratives. Her knowledge of French and Italian meant she could translate, or in our current sense summarize, these plots and provide deeply informed literary analysis and commentary for English readers.

It has long been known that Shakespeare wasn’t original; that is, his plots were not fully formed from his imagination alone. Borrowing from earlier authors was also not surprising to anyone at the turn of the eighteenth century. In fact, most authors during Shakespeare’s time created stories that had some basis in the plots of those that came before. As a published author herself, Lennox was interested in authors’ craft and thought it important that audiences know in detail just how Shakespeare had borrowed. Her comprehensive source analysis was the first of its kind.

In addition to her thorough presentations of each text, what distinguished Lennox’s work from her predecessors was that, rather than a catalog of titles that Shakespeare had drawn from, Lennox gave her readers the actual source texts, either in summary form or in translation; and after each, she provided commentary and critical notes to explain the ways in which he altered these original plots. Promoting newly emerging literary values of originality and concepts of authorship, she strove to be factually accurate and meticulously faithful to her standards of novelty, which included the belief that authors should be innovative, if not original. This was not universally believed, as imitation was still—in many circles—thought to be the highest form of compliment. As a crafter of plots herself, Lennox criticized Shakespeare’s ability to adapt judiciously, adopting the neo-Aristotelian principle of probabality. She wasn’t derisive of the fact that he borrowed others’ plots, but she was recklessly frank about how unconvincingly he had done so.

Still, Lennox valued many of Shakespeare’s contributions. She praised his Macbeth as “a most beautiful piece” and noted his clever move to adapt Holinshed for political purposes (I: 292). Yet she also illustrated how Shakespeare was not only unoriginal, but using prior sources to adverse effect. For example, he employed Lodovico Ariosto’s sixteenth-century epic poem and heroic romance Orlando Furioso (specifically the fifth canto, “Tale of Geneura,”) to construct the Claudio-Hero plot in Much Ado about Nothing. According to the twentieth-century source scholar, Geoffrey Bullough, “The story of the Beatrice and Benedick is usually more interesting to modern readers than that of Hero and Claudio, but the latter is the core round which the other was wound, and to trace the provenance of the Hero-Claudio actions throws light on Shakespeare’s conception of his play and also on his manner of blending sources” (II: 62). The Claudio-Hero plot has numerous variants. In Ariosto’s version the end of Canto IV centres on Geneura (an alternate spelling of Guinevere), daughter of the King of Scotland and her true love Rinaldo (Hero and Claudio respectively in Much Ado). Lennox identifies a failure in Shakespeare’s characterization of Don John, who is part of a plot to stage Hero’s supposed betrayal of Claudio. Lennox maintains that Shakespeare did not provide enough of a motive for Don John to persuade Hero’s waiting woman to double cross her:

Margaret is all along represented as faithful to her Mistress; it was not likely she would engage in a Plot that seemed to have a tendency to ruin Hero’s Reputation, unless she had been imposed on by some very plausible Pretences, what those Pretences were we are left to guess, which is indeed so difficult to do, that we must reasonably suppose the Poet himself was as much at a Loss here as his Readers, and equally incapable of solving the difficulty he had raised.

Lennox describes Shakespeare’s one-dimensional Don John “as a Villain merely through the Love of Villainy (III: 262-3).” In contrast, Ariosto had detailed Don John’s ambition and need for revenge, thus creating a more believable scene. How Margaret is “imposed upon” and why Don John devises a plan that requires Margaret be seduced is a question grounded in Lennox’s interest in understanding evil. Lennox is also pointing to the way that Margaret is treated by Shakespeare and asking what reason she would have for being unfaithful to Hero. Today lack of motivation is seen as lifting Shakespeare’s work above his sources by adding complexity and depth, but Lennox was of the school that believed audiences wanted to understand a characters’ drive.

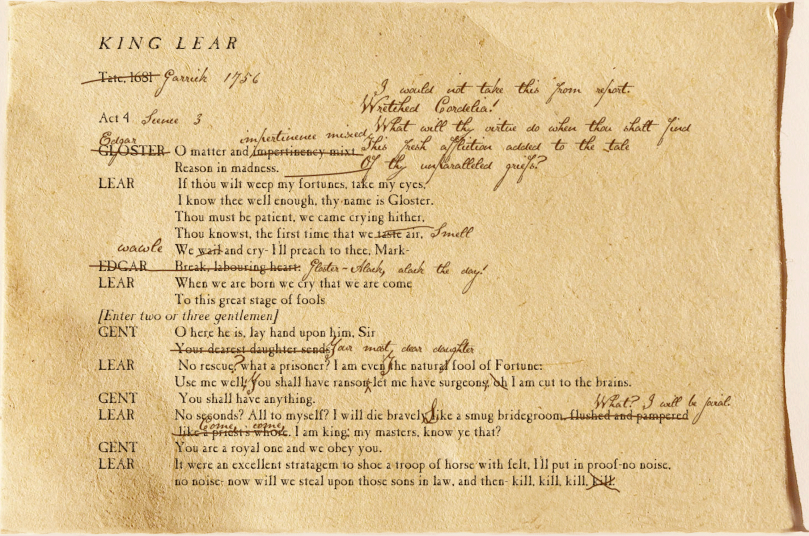

In keeping with this theme of believability, Lennox also describes Shakespeare’s “utter disregard to probability” (III:267). She argues that he did not represent the ways people actually behave, nor did he satisfy his audience with explanations of those behaviors. For example Lennox writes in detail about Shakespeare’s injudicious adaptations from Holinshed of “the fable” of King Lear. Cordelia, whom Lennox describes as having “Greatness of Soul,” is only disinherited in Holinshed for her “noble disinterestedness.” Lennox critiques Shakespeare for instead having Cordelia’s father conduct “an absurd Trial (III: 288)” [the love test], banish her to poverty. This cruel treatment of a daughter makes no sense to Lennox, as it makes Lear only seem mad: “what less than Phrenzy can inspire a rage so groundless, and a Conduct so absurd?” (III: 287).

Lennox had a high opinion of the intelligence of audiences and frequently did not accept Shakespeare’s violation of what she deemed credible. She explains, “So unartfully has the Poet managed this incident” that Cordelia has to “seek rather to free herself from the Suspicion of Guilt, than modestly enjoy the conscious Sense of superior Virtue” (III: 288). Lennox is interested in power relations, and here she shows Shakespeare’s lack of practicality in exchange for shock value… and at the expense of an honorable woman. One year after Lennox’s critique, Shakespeare actor and powerful theater manager David Garrick, added lines to the play that are more sympathetic to her plight. Rather than following Nahum Tate’s (1681) adaptation of Act IV, Scene III, Garrick who had frequently worked with Lennox wrote in more sympathetic lines for Cordelia.

Today, Lennox’s extraordinary Shakespeare scholarship has been overshadowed by Samuel Johnson, who eleven years after Lennox, published The Plays of William Shakespeare (1765). Jacob Tonson and his associates, the publishers for the renowned Shakespeare scholar William Warburton controlled the rights to the current edition of Shakespeare. Tonson et. al. granted Johnson the right to publish. Yet it took a mysterious nine years for him to complete, perhaps because Johnson felt pressure to idolize Shakespeare. Still, his edition would be cited as the publication that canonized the bard.

Reviving Lennox’s groundbreaking contribution to Shakespeare studies is long overdue. Offering her readers another vantage point based on carefully presented and parsed evidence, Lennox recognized that what constitutes “good” literature was an evergreen subject for heated debate and would be relative to a critic’s subject position. With a scholar’s eye, she considered expectations for what the English canon should contain and who an English genius was. She was rewarded by being recognized as an important contributor to Shakespeare studies by dozens of succeeding Shakespeare scholars, from the popular and prolific late eighteenth-century commentator George Steevens (1:466) to the romantic literary icon Samuel Taylor Coleridge (in 1811-1812; p. 219). In the twenty-first century she appears in many of the iconoclastic literary critic Harold Bloom’s twenty-one volumes of Shakespeare criticism and is now placed in the pantheon of important early American theater critics.

Shakespeare emerged from Lennox’s pen not as a literary hero, but as an author worth studying and critiquing. Until 1790 Lennox frequently engaged with questions about literary value, not least in her novels and plays, and published 15 more works, including groundbreaking translations of the memoirs of the principle advisor to Henry IV, Maximilien de Béthune (1756) and of Pierre Brumoy’s Le Theâtre des Grecs (1759), as well as a magazine commited to engaging women’s minds in intellectual pursuits (1760).[1] With an eye to future audiences Lennox deftly participated in the Enlightenment deliberation about what constitutes a genius and how he (or she) is selected. In the 1750s her Shakespear Illustrated articulated the newly evolving literary value that genius is a relative quality, that the characteristics associated with it require reassessing, that more minds should be taken seriously, and that perhaps some overlooked ones deserve glorifying.

Susan Carlile is a Professor of English at California State University, Long Beach. Her book Charlotte Lennox: An Independent Mind was published in 2018 by University of Toronto Press. She was a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellow and has held fellowships at the Huntington Library and the Chawton House Library. You can follow Charlotte Lennox and Susan Carlile on Twitter.

Further Reading

Bennett, Alma. American Women Theater Critics: Biographies and Selected Writings of Twelve Reviewers, 1753–1919. McFarland, 2010.

Bloom, Harold. Bloom’s Shakespeare through the Ages. Chelsea House Publications, 2007.

Bullough, Geoffrey. Narrative and Dramatic Sources of Shakespeare. Columbia UP, 1957-75.

Carlile, Susan. Charlotte Lennox: An Independent Mind. U of Toronto P, 2018. https://utorontopress.com/ca/charlotte-lennox-2

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. Lectures and Notes on Shakespeare and Other Dramatists. Oxford, 1931.

Dobson, Michael. The Make of the National Poet: Shakespeare, Adaptation and Authorship, 1660-1769. Clarendon, 1992.

Doody, Margaret Anne. “Shakespeare’s Novels: Charlotte Lennox Illustrated.” Studies in the Novel, vol. 19, no. 3, 1987, pp. 296–310.

Gevirtz, Karen. “Ladies Reading and Writing: Eighteenth-Century Women Writers and the Gendering of Critical Discourse.” Modern Language Studies, vol 33, no 1/2, Spring-Autumn 2003, pp. 60-72.

Green, Susan. “A Cultural Reading of Charlotte Lennox’s Shakespear Illustrated.” Cultural Readings of Restoration and Eighteenth-Century English Theater, edited by J. Douglas Canfield and Deborah C. Payne, U of Georgia P, 1995, pp. 228–57.

Hume, Robert. “Before the Bard: ‘Shakespeare’ in Early Eighteenth-Century London,” ELH, vol 64, no1, Spring 1997, pp. 41-75.

Kramnick, Jonathan. “Reading Shakespeare’s Novels: Literary History and Cultural Politics in the Lennox-Johnson Debate.” Eighteenth-Century History: An MLQ Reader, Duke University Press, 1999, pp. 43–67.

Ritchie, Fiona. Women and Shakespeare in the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Scarsi, Selene. Translating Women in Early Modern England: Gender in the Elizabethan Versions of Boiardo, Ariosto, and Tasso. Ashgate, 2010.

Steevens, George. The Dramatic Works of William Shakespeare. Bulmer and Co, 1802.

Thompson, Ann and Sasha Roberts, eds., Women Reading Shakespeare 1660-1900: An Anthology of Criticism, Manchester UP, 1997.

Vickers, Brian, ed. Shakespeare: The Critical Heritage, Volume 3, 1733–1752. Routledge, 1975.

–. Shakespeare: The Critical Heritage, Volume 4, 1753-1765, Routledge, 1975.

[1] All of Charlotte Lennox’s works:

Poems on Several Occasions (1747)

The Life of Harriot Stuart, Written by Herself (1751)

Memoirs of Maximilian de Bethune, Duke of Sully, Prime Minister to Henry the Great (transl. 1751 abridged and 1756)

The Female Quixote (novel, 1752)

Shakespear Illustrated (literary criticism, 1753-4)

The Memoirs of the Countess of Berci (transl., 1756)

The History of the Count de Comminge (transl., 1756)

Memoirs for the History of Madame de Maintenon and of the Last Age (transl., 1757)

Philander (play, 1758)

Henrietta (novel, 1758)

The Greek Theatre of Father Brumoy (transl., 1759)

The Lady’s Museum (magazine, 1760-1)

Sophia (novel, 1762)

The History of the Marquis of Lussan and Isabella (transl., 1764)

The History of Eliza (novel, 1767)

The Sister (play, 1769)

Meditations and Penitential Prayers (transl., 1774)

Old City Manners (play, 1779)

Euphemia (novel, 1790)

I’m no Scholar, but this is fascinating! Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you. It thrills me to see this comment. Please spread the word ;-).

LikeLike